Extended Stay Hotel.

Day one.

We are coached to practice communicating our boundaries. We are instructed to stay with the sensations of the body, to bear compassionate witness to those in our midst. To hold space. We feel bonds happen at a rapid pace, even though we don’t see one another’s face without a mask for days. We stumble and grapple with are-we-doing-it-right?

The first night at the hotel was a shock to the system. The parking lot was such that I had to walk many paces from car-to-door; workermen trucks were hogging all the spaces that were remotely close to my 2nd floor room. I was forced to a dark corner beneath an unpruned Russian olive, with gangly branches that seemed to reach out and grab at my clothes like witch fingers when I opened the car door. Early on, I decided to mention to as many people as possible where I was staying. Just in case. My mom had given me pepper spray when I visited in August—why? I’m trying to remember. Oh, because I parked in an airport shuttle lot and needed to retrieve my car at night. But that particular shuttle lot felt safe, regarded. I didn’t even pull the spray out of my suitcase, and I admit I was relieved to find it still in there for this very occasion.

My hotel room felt like it needed an exorcism. The air was thick and waxy, like when you cover your face with a blanket then take it off to feel the cool crisp aliveness of fresh air. This room, this space, was without the breath of fresh air. The windows did not open so I blasted the A/C window unit to at least get something moving. I wiped every surface with my handwipes as if I could wipe out the building’s history of dysfunction and lack-of-care.

The cupboards of my little kitchen were barren, like that nursery rhyme: Old Mother Hubbard. Utterly empty. There was nothing in me that wanted to ask for a thing or two from the front desk, so I bought dish soap and a sponge from Walgreens the next day and made my way through by washing and reusing the containers things came in. A pre-made container for a sandwich wrap from Whole Foods would be reused multiple times for homemade PB&Js. A washed-out yogurt container would be recycled for granola the next morning. It all felt sparse, rationed, rather than environmentally conscious.

In the mornings, I propped open the door with a chair which felt like airing out a wound. I named the flies that found their way in. But by lunch, about a half-dozen workermen had gathered to smoke, huddled together in their neon shirts like a Day-Glo smoke stack. The smoke wafted directly through the gap of my propped-open door. So, I didn’t linger.

Day two.

Our teacher writes this phrase on the dry-erase board: Healing from trauma can feel unsettling, as if you are walking into a building that is being demolished and rebuilt at the same time.

We are tuning in to the sensations in our bodies. I am annoyed with my body, the music inside my skin sounds like dead-air, late-night tv programming gone-to-snow. I wait next to the phone for a ring while overhearing my classmates describe their sensations using words like melting-honey and cold-metal-rod. I am finding it very difficult to trust the process of my own body.

I couldn’t see it at night, but at first glance in the daylight, the grounds around the hotel appeared to be a festive after-party of yellow confetti. But a closer look revealed that it was in actuality hundreds of cigarette butts on the sidewalk, littered in the rocks of the landscaping and peripheral shrubbery. If I were a smoker in the midst of this, I have to admit how futile it would seem to be the one to walk to a trash can to dispose of my butt, how I may feel like a minority, judged for caring. Flattened beer cans were also a thing, stomped and abandoned, aluminum pocks on the sidewalk and stairs.

Day three.

We talk about the neurology of trauma. Then how, when someone is in survival mode, the last thing he is concerned about is disposing of a cigarette butt or beer can properly. And if someone is unable to give their trash the tending it requires, imagine his relationship with his wife and family.

And then I had a haunting thought: our planet will burn to a crisp because such an enormous percentage of people are traumatized and barely surviving.

I tell a lady in my class that I am staying at the Extended Stay and she tells me about a podcast she loves, where a husband-and-wife team solve crimes. Their most frequent place for stakeouts is an Extended Stay! She laughed.

A young couple stayed in the room right below me, with their toddler son. As I returned to my car after lunch, he sat on the dirty sidewalk and played alone with a polyester Paw Patrol dog. There was an overflowing ashtray next to the door. I made the mistake of saying hi to the little boy as I passed, not seeing his mom’s boney arm extended with a burning cigarette from a partially opened door. Her face was pale and pocked-marked, like Halloween make up. Startled, I smiled at her, and the look she gave back was a cauldron of rage and contempt. (I did not say hello to the little boy anymore.)

Day four.

We learn in class that how we handle stress can be hereditary, ancestral. That our experience in utero has an impact as to how well we can process traumatic situations. So, presumably, a human can have two strikes against them before even taking their first breath.

We also talk about how insights rarely happen when we are chasing them down.

Occasionally, I drove my car the other direction on Wadsworth, to where the money was. I had lunch at Whole Foods and upgraded my masks at a high-end sporting goods store—took a break from the hotel, from feeling like I was either under a blanket, breathing car exhaust or gonna get assaulted for being friendly. It occurred to me that we don’t think about our own safety when we are accustomed to feeling safe in our environments. But what if, as RuPaul says, what if the call is coming from inside the house? What if we feel utterly safe in our world but are starting to notice that we don’t feel safe in our own body?

In class, we learn that dysregulation creates noise. Our aim is to dampen that noise. Our survival tactics keep us alive until, suddenly, they keep us from living.

There was a tall man-boy I frequently saw at the hotel. He moved like a gazelle, undomesticated, walking on toes (hooves), shifty-eyed and scattered. I couldn’t help but make an assessment even as I made my way passed him to my room. I realized, already I cannot take this work out of my bones. It’s like being granted x-ray vision—but you don’t get to give it back.

There is a certain painting in our house that, when hung on the proper wall—with a backdrop of the proper wall color and good lighting—it is a masterpiece. And yet, when hung in a corner on a white wall, it is, well, nothing special. No thing exists is a vacuum. A thing is unquestionably shaped by what surrounds it.

There are sixteen students, four TA’s and a teacher. We all left the school building during meals and at night. I considered that what/who filled the space while out of school cast a certain hue on the space of actually being in school. (The space between the words, as it were). How did it feel to return to an AirB&B during breaks, some with a host who requested social time, and others just a quiet, empty place. One of my classmates stayed at a fancy hotel next to Whole Foods. I wonder if she enjoyed the break from her school day to brush elbows with Patagonia fleece? If she relished the abundance, or did she have an uncomfortable kind of exchange with someone who may have interpreted such luxury as entitlement. And did she need to reconcile her assumptions before returning to another day studying trauma in the body?

Day five.

The final morning: As I packed up my car before the last ten-hours of class, I noticed a man exiting his room a few doors down that I mistook as a priest. I was shlepping a yoga mat and a reusable grocery bag and feeling a little embarrassed by my overt cues at health and environmental thoughtfulness. For a flash, this man, this priest, felt like a kindred spirit in this hazardous living space that seemed to hinge on not-caring, not-tending. A man of the cloth. He was carrying a half-bag of laundry the opposite direction so I quickened my pace to catch up to him.

I offered a good morning to the priest and he swung around as if what I’d actually offered was a swat on the back of the head. I may have jolted back in reaction to his defensiveness, his odd fear, as if he was part of a game I could not see. I wrapped my fingers around the keys in my pocket. His face was not-at-all that of a friendly like-mind; it was that of a tortured animal. He had the kind of glasses that made his eyes creepily large, cartoonish. His cheeks were rosy and flakey, perspiration framed his swollen face. And he was obviously not a priest, simply a man wearing all black. How hungry must I have been for a relatable neighbor to create such a convincing story.

A recently-read Brene Brown quote comes to mind. (Brown is a professor at the University of Houston Graduate College of Social Work, specializes in social connection.): “A deep sense of love and belonging is an irresistible need of all people. We are biologically, cognitively, physically, and spiritually wired to love, to be loved, and to belong. When those needs are not met, we don't function as we were meant to. We break. We fall apart. We numb. We ache. We hurt others. We get sick.”

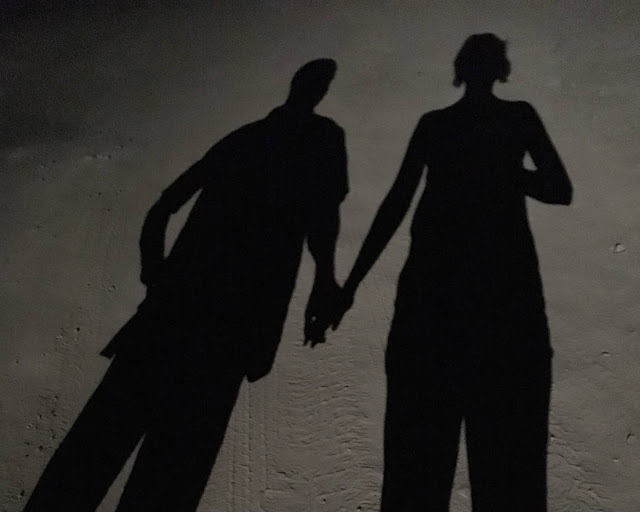

I would arrive to school in a matter of minutes on that final day, and we would discuss how you cannot heal from trauma in isolation, it simply is not possible. How human connection is hands-down the best thing for your health. I reason that the Extended Stay demographic is as deserving of that level of human connection, that level of care, as are my unique and varied classmates, as is the rich lady at Whole Foods. As am I.

Comments

Post a Comment