FAMILIAR FACES

The origin of the word, familiar: Middle English (in the sense ‘intimate’, ‘on a family footing’): from Old French familier, from Latin familiaris, from familia ‘household servants, family.’

~~~

A few weeks ago, I stumbled on this article in New York Magazine.

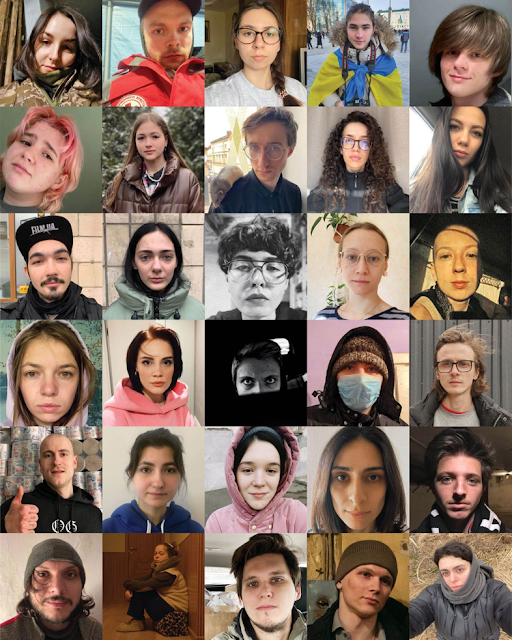

Thirty young Ukrainians describe daily life during the first 16 days of the Russian invasion. I copied the main photo to my desktop and made it a practice to study The Faces, examine the glasses, the clothing, the expressions, the posturing. It's become a multiple-times-a-day thing. I planned to write something immediately, but two stomach bugs, a cold, and spring break demanded my attention elsewhere. At that point, the war had been going for 16 days. By now—Wednesday, my kids safely back to school after a pleasant spring break—the war is in its fifth week. Some of these thirty faces may no longer be attached to a pulse.

In looking at The Faces, I see myself as a twenty-something, I see Opal in ten years and Ruth in twenty, I see young adults with hearts and minds and families. With modern irritations and varying afflictions. They are braiding their hair and making breakfast and finding their respective voices in the midst of sheer disaster—the same way any of us would.

One of the young ladies looks like my niece in Cleveland. Lingering on her photo—with the puffy hood and a Ukraine flag wrapped around her shoulders—nearly brings me to tears. The familiarity. And that's what I want: to feel some connection to the individual players of this current nightmare. A hot flicker of emotion makes it seem like she can almost hear me. How else do I let her know she is not alone? But does taking the time to consider her—them— while safely sipping coffee in my apartment, count as enough? I will move on to playing catch-up from a week with the kids at home. They will go on trying not to die.

~~~

Petro Chekal, 20, a student in Kharkiv, said "We told my grandmother we wanted to leave, and she said, “How are you going to leave your home?” My grandparents refused, no matter how much we begged them. We got to the railway station and men weren’t allowed on the train. I could hear these soul-rending screams of women who had to leave their men in a city that was being bombed. In Lviv, our friends lent us a three-room apartment. We’re drawing the curtains out of habit and turning off the lights so the enemy can’t see where to aim."

~~~

Julia Berdiyarova, 28, a museum worker in Kyiv and Odesa said: I didn’t bring much: clothes, documents, all my money. I was sure I’d be here only for a week and after that I’d come back to Kyiv again, so a lot of things that I need I left behind. And I feel sad because little things like sculptures or books, these poems that I want to read now, stayed there. But my mother told me, “You took yourself, and this is the most important thing you take.”

It is still devastating to drive by the huge swaths of land in our community that were torched by the Marshall Fires three months ago. Entire neighborhoods scraped clean. One life after another of memories, keepsakes, property, homes: cremated. My heart still swells as I drive to the grocery, to school, as if that land is now a melancholy charnel ground. Not of lives—thank goodness—but of futures, of pasts, of safety.

We evacuated that afternoon because our friends did, not because of any real information or an evacuation order. It was confusing and slightly chaotic. We thought we'd be gone for a few hours, none of it felt real. How could it be real? Forests burn in the heat of summer, we get that. But an Urban Fire right after Christmas that took down a hotel right off the freeway as if it were kindling? I grabbed yoga pants and two beers for myself, plenty more for my six-year-old, Ruth, and the dog. I thought we'd be home in a few hours. Twelve-year-old Opal meticulously packed an overnight bag and in the hustle of gathering, it was forgotten at the house.

“You took yourself, and this is the most important thing you take.”

After we evacuated to a friends' house, we were glued to our phones, in spite of that being the last place we wanted to be. That's where the news was. That's where the onslaught of messages from fearful loved ones, friends, acquaintances, were: ARE. YOU. OK? I quickly got overwhelmed by the amount of texts I felt I was on the hook to reply to, even as I wasn't sure if our house was still standing. Jesse said I needed to make a template, to simply cut-and-paste a reply. But when I texted a male stranger who had my number from a pick-up he'd done from Craigslist and who had texted to see if I was ok, "Hey mama. We are safe. Love you so much" (plus three heart emojis), it became clear that my brain was running on a collection of frayed threads.

That was mere hours after the evacuation. In another twelve hours; we were safely staying with family in Boulder, our house was still standing and I could still barely squeeze out a complete thought.

~~~

Katya Vasiukova, 26, an actress from Kharkiv, said,"The first days were calm, but then several houses were burned down. My friend found a driver, and I had 15 minutes to pack. In Lviv, my friend Anton received me. Different families had settled in his house. It was interesting to watch the children, my own and others. There was a box of military toys in great demand. The children played war and said phrases they heard from the news or their parents, like “The bombs are flying,” “Attack.""

~~~

The children. Considering children during war is particularly wrenching. My fingers don't want to type it. My mind doesn't want to entertain the possibility. But recognition is part of the tragic equation. These kids are no different from my own. The moment my mind wants to register the images on the screen as detached, far-off, two-dimensional, and other, a tiny alarm goes off in me and I need to make them flesh and real. I walk over to my daughter and touch her arm and maybe I lag a minute and try to soak up her human-ness in the space with me, her flesh and bones and blood. The air we both share. I don't want to detach from suffering. I don't want to be desensitized.

~~~

Lesyk Yakymchuk, 29, a graduate student returning to Kyiv from Ohio: "On one hand, Kyiv is the same city I used to know. But it’s also a different, cold city. There’s not many people out, not many cars. No one turns on their lights at home. It’s postapocalyptic, a bit, but I’m still feeling that I’m at home."

~~~

Community grief in Louisville still lingers in the air like low fog. I don't want my eyes to grow used to the entire neighborhoods that are charred and erased. I don't want to forget what our town was before that day. It's not the same as a battlefield—again, no bodies—but it's the first time I've lived within a landscape that is deeply wounded, tragically altered. We can't go back. Our dear friends who lost everything cannot go back. Healing—and supporting others in their healing— is on the forefront of my mind. Repair and empathy are vocab words used so often that I've actually started replacing them with —lesser-used, more vibrant?—synonyms.

(Repair: mend, put right, restore, renovate, rebuild, reconstruct, mend, service, improve. Empathy: affinity with, rapport with, sympathy with, understanding of, sensitivity towards, identification with, fellowship with, awareness of.)

Tell me, what does five weeks of war do to a mind and a body? To describe such senseless gore, the written language would need to bleed, to moan, to crumble, to emanate a stench that invades every inhale. What must it feel like to see no end to it? The words repair and empathy must feel unfathomable to them, a garbled mockery. But it is my hope that no single person is completely void of at least occasional moments of peace. Is that naive?

~~~

Markiian Matsiiovskyi, 28, a DJ and film director in Kyiv said "I moved in with friends and made a post on Instagram to collect donations to buy supplies for the Territorial Defense. Food, energy drinks, cigarettes — the last made them particularly happy. One time, I was in the checkout line when the siren went off, and I did not care because I had to buy food that people needed. I’m a workaholic by nature, and knowing that what I do is needed by others brings me comfort. I don’t earn any money from this. We don’t speak in terms of weekdays and weekends. When we started our work, we understood there couldn’t be any days off. I named our group An Object Under Angels’ Protection, and I want to think we are, in a way, angels."

I notice one of the men in this photo is wearing Crocs, the color of tahini, with black socks. Jesse wears black socks with his sandals, too. Crocs are manufactured in Boulder, minutes from our house. In fact, every child and teacher in the BVSD (Boulder Valley School District) got a free pair after the Marshall Fires.

The longer I examine these images, the more similar we all become.

~~~

...knowing that what I do is needed by others brings me comfort...

Empathy is not drawing comparisons. It is not feeling sorry for someone. It is feeling with someone and requires a slowing of the mind to do as much, to let it in. Of course, the particulars of any situation will be different, but the real truth is we are hard-pressed not to find common ground with someone who is suffering, across the kitchen table or across the world.

And I need to wrap myself in this notion right now, a weighted blanket to offset the spin-cycle of thoughts: how do I help? what in the HELL can I do when there is just so much suffering?

A good starting place seems to be to recognize that we are not alone in our suffering, as they are not alone in theirs. At any point in time, there will always be someone familiar within arm's reach who needs the same recognition, the same consideration, I've been giving these thirty young Ukrainians in the photo.

Any single contribution towards peace, any offering of empathy or caring action in my little part of the world has to matter.

Because that is what—and all— I can do.

Comments

Post a Comment